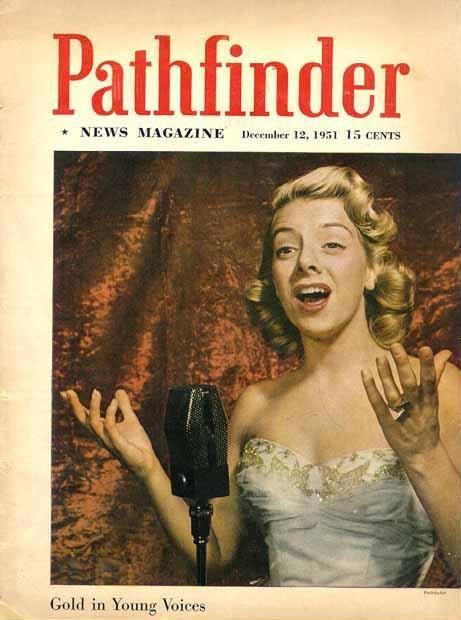

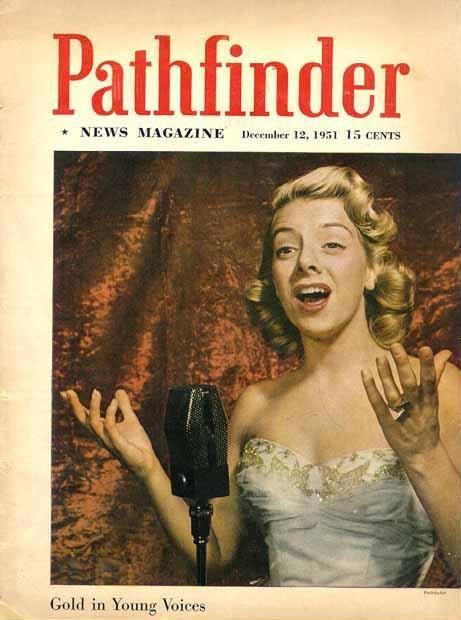

GOLD

IN YOUNG VOICES

GOLD

IN YOUNG VOICESSingers just old enough to vote make

most of today's popular record hits

GOLD

IN YOUNG VOICES

GOLD

IN YOUNG VOICES

Singers just old enough to vote make

most of today's popular record hits

By John M. Conly (Pathfinder, December 12, 1951)

Submitted by: Roger Rubens

"Could I get just a sandwich, Dan?" pleaded Tony Bennett. "I haven't had anything to eat since breakfast."

Dan Stevens, Columbia Records' East Coast promotion manager, looked at his watch. "No," he answered heartlessly, "You're due on stage at 6:15 and it's nearly 6 now."

Bennett grinned, shrugged and accepted a chocolate bar from a softhearted newspaper reporter. He offered half to ROSEMARY CLOONEY. Busy signing phonograph records in white ink for breathless teenagers, she shook her golden head : "I had a malted, Tony. You eat it."

"Sweet kids," said Stevens -- fondly, as befits a man talking about a half-million dollar property. Then he herded the sweet kids out of the record-shop and back to their dressing rooms in Loew's Capitol Theater, Washington.

While they got ready to go out and sing in the 6:15 stage show, Stevens went through his notebook, checking the rest of their evening's schedule. There were calls on two disk jockeys; a visit to a wounded-ward at a military hospital; a "casual" drop-in at a leading night spot; the late stage show, then bed.

There would be a week of this, and Stevens had two more Columbia men along to make sure the nation's capital got the full impact of the Clooney-Bennett visit. At the time, ROSEMARY clanging, bouncing record of Come On-a My House was moving toward the million-sales mark. Tony's Cold, Cold Heart and Because of You were just establishing semipermanent residence at the head of the country's popular best-seller lists.

The sweet kids were at the top. But they had reached it almost overnight. To keep them there was the purpose of their personal appearance tour, with its 17-hour working days, and of the tireless skirmishing of the Columbia promotion-men with them. ROSEMARY and Tony, together with two other young Columbia songsters, Guy Mitchell and newcomer Johnnie Ray, had sold some six and a half million records within a year. Young voices on ballad-records had suddenly become very big business.

|

|

|

Between songs. |

This' wasn't a one-company phenomenon, either. Mercury Records' great 24-year-old, Patti Page, had set an all-time one-year one-disk record with Tennessee Waltz --nearly three million sales. Capitol's clever, unpretentious "young marrieds," Les Paul and Mary Ford, had piled hit on hit for a total of almost five million sales in 1951.

RCA Victor was busily pushing Eddie Fisher. April Stevens, June Valli and Merv Griffin, all in their early 20's. Mercury had Tony Fontane and Bobby Haynes to back up the fabulous Patti. M-G-M's roster featured Cindy Lord, 20, and Fran Warren, 24. Decea had Ronnie Gilbert, Don Cherry, Jane Turzy, Tamara Hayes. Capitol, in addition to the Paul-Ford gold mine, had sweet-voiced Gisele MacKenzie and Bob Sands.

These young vocalists, some of them hardly more than children, and their songs--bouncy, folksy or sentimental, but always simple--were now the mainstay of what the record trade calls the "pop" business. This doesn't include "folk" records (hillbilly and Western) or "race" (blues and rhythm, by Negro performers). In general, the true "pop" is aimed at listeners in no special place or grouping--except possibly an age-grouping. It was youngsters, back in the 1930's, who originally put Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, Goodman, the Dorseys and other dance-music stylists on top of the lists. It is still youngsters who start the fads in record-buying--and stop them.

Upset. They put an end to the bandleaders' reign shortly after World War II. Prior to that, a name-band with its own special musical arrangements was almost a necessity to a hit-record. A disk made with only a studio band was automatically classified as a "B" production. Now the studio band, often led by the studio's artist-and-repertory manager, is part of the standard formula for a sure-fire hit. Its function is to play background for a 24-year-old singer who may not even be able to read music.

Just how this happened, nobody knows. Red-headed Fran Warren, who got her musical education singing with bands ("swing from Charlie Barnet; sweet from Claude Thornhill") says the bands offered too much of the same thing too long: "Even the best candy. you can't force down people's throats." Booking agents think the trouble is that today's younger generation doesn't know how to dance, which they blame on the war.

Whatever the cause, danceband music suddenly lost its youth-appeal. Hillbilly records began to fill the gap, invading city markets. New York recording directors hunted desperately for something with which to fight back. What they finally found was the young "personality" singer.

Country-Style. It is no accident that a touch of hillbilly quality crops up in many new "pop" hits. Les Paul, of course, was a hillbilly singer, under the name of Rhubarb Red, for some years. Clara Anne Fowler, better known as Patti Page, began developing her singing-style on the Page Dairy radio program (hence her pseudonym) in Tulsa. The smoothed-up semi-country flavor of Tennessee Waltz is what she finally worked out as best bet for general acceptance today. Her unerring hit surprised no one who knew her. Ever since she learned algebra in her spare time in grade school, for fun, there has been no doubt that Patti has brains.

In a sense, both Patti and Les Paul, who comes from Waukesha, Wis., worked out their styles in half-country, half-city listener areas-then brought them to town when the time was ripe. Both are natural experimenters: it's significant that, at about the same time, each of them began experimenting with tape-recorders in the same way, making double, triple, even quadruple-voiced recordings in which they harmonized with themselves. Paul now makes all the Paul-Ford recordings on his own machine, turning the finished tape over to Capitol engineers for disk-cutting.

Talent-Tailors. More truly typical newcomers in the young vocalist department haven't had to work out their styles themselves this way. That's up to the record companies' artist-and-repertory directors, who fit singer-to-song-to-treatment. Most celebrated of these is Columbia's Mitch Miller, who has launched, all in the past year. ROSEMARY CLOONEY, Tony Bennett and Guy Mitchell.

Miller, a stocky, kinetic man with a beard, is often referred to as a genius and seldom argues about it. He is one of the world's best oboists (classical or popular), one of the leading makers of children's records (Little Golden Records) and an almost infallible picker of tunes and talent.

|

|

Asked which comes first, the singer, the song or the special musical treatment, Miller says "the idea." The idea, in records made by the newly-come youngsters, is usually to keep the finished product from having too much finish. It should have some imperfections, to keep it informal, personal and endearing. Tony Bennett, for example, sometimes sings a little flat, especially in melancholy ballads. This should be treasured, says Miller; it keeps Bennett sounding like "the boy down the street, singing with a slight tear in his voice."

Miller loves working with new "kids," because, as he puts it, "they have nothing to lose"- no established styles or reputations. So they'll let him experiment. Purely experimental was the slam-bang pace he set for ROSEMARY CLOONEY ("wonderful girl, she can do anything from barrel house hillbilly to blues") and Stan Freeman's harpsichord in Come On-a My House.

To be good experimental material, what a young singer needs most is personality and natural charm. Musical know-how can come later.

And, without exception, the successful ones do have charm. It is quite possible not to enthuse over Eddie Fisher's upper-throat warbling, for instance. But people find it very hard not to like slight, winsome, 23-year-old Eddie himself. This goes even for his 80-some comrades in the Army Band, who are all sergeants, whereas Eddie (one of two draftees in the outfit) is a lowly Pfc. To make the most of this Fisher-appeal, incidentally, the Army has him constantly on recruiting tours, with emphasis on Wacs.

(Had it been male recruits they were after, their best bet would have been Eddie's fellow Victor-artist, pert, provocative April Stevens, 21, whose I'm in Love Again has stirred GIs in training camps almost to riots.)

There is no sameness, however, in the youngsters' tastes. Eddie Fisher loves Puccini operas. Tony Bennett listens to Bela Bartok concertos. Guy Mitchell twangs Western ditties on a guitar. back-stage, or bellows rhythmic Yugoslav folk songs. Both come natural; he's an ex-cowboy of Yugoslav descent, really named Al Cernie. At 15 he broke his first bronco, bought with $25 he earned as an apprentice saddle-maker.

Tot-Magnet. ROSEMARY CLOONEY's immediate vicinity is always cluttered with children, borrowed from friends and relatives. They fascinate her (her favorite work is making Columbia children's records) and she them. Someday she aims to have some of her own, hut she's Irish and doesn't believe in show-business marriages. First she has to fulfill a movie contract, with Warner Bros. Then maybe she'll think about it. Columnists link her name with TV star Dave Garroway, but she says she hasn't known him long enough to be serious: "and, besides, we never are serious." Last summer at Long Island's swanky Bridgehampton sportscar races, ROSEMARY stood in the Garroway mechanics' pit, holding up cards marked "Lap 12" and "Lap 13" as Garroway's Jaguar flashed by. Suddenly she giggled, began scribbling with a crayon. Next time around, instead of "Lap 14," Garroway read: "Don't hurry; your option's been picked up."

No Deadheads. Like many of the new-vocalist crop, ROSEMARY can't read a note--but she can learn a song, cold, in 15 minutes. That's talent -- but so was Gisele MacKenzie's prodigy-record as a violinist at Toronto's Royal Conservatory. So was Tony Bennett's learning to sight-read while turning pages for a friend who played cello in a neighborhood string quartet. The friend, Sam Katz, was also a popular hand leader. It was he who got Bennett to think seriously of singing. Bennett had first studied to be an artist, then to be an actor. Probably he could have succeeded at all three. He still draws very well. (So do Patti Page and Fran Warren.)

Mitch Miller figures that the average successful "pop" singer can count on five years at the top. A new generation of teenage record buyers will come into action then. Rare is the Dinah Shore or Jo Stafford who can go on and on. Most of the young pop-hit clan have no illusions about this -- but plenty of plans. They purposely think of themselves as being in show business, rather than music. Tony Bennett has his American Theater Wing training. Fran Warren toured last slimmer with a road company of Finian's Rainbow . ROSEMARY has the movies-and a timeless standby -- children's records. TV offers possibilities to all ("but you have to be an entertainer there, not just a singer").

Conversely, the pop-record business attracts show people as well. A newcomer to the Decea stable is Dolores Gray, 25-year-old musical comedy sensation who captivated London in "Annie Get Your Gun" and now co-stars in New York in Two on the Aisle. Her first pop record Shrimp Boats is competing not too badly (in New York, at least) with the Jo Stafford version. At Columbia, Mitch Miller has been grooming Carol Channing, star of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. If either of these fails to make a disk hit, it probably will because they're a little bit too good -- no imperfections. Even friendly disk jockeys (and they are the prime popularity medium for "pops," with juke boxes second and nothing else in the running) can't put a singer over if the youngster-public doesn't get what it wants.

Sometimes the young customers pick out a new favorite before the jockeys spot him. Gene Klavan, who simulcasts an "after midnight" d-j show from WTOP-TV (CBS-Washington), a "clear channel" wide-coverage station, held a studio audition last year. Klavan, who thought he knew all the top favorites (he listens to every record he gets-sometimes hundreds a month) was puzzled at the strange, high delivery of some of the boy hopefuls. It took him several minutes to figure out that they were imitating a brand-new singer Eddie Fisher. "l knew then that Eddie was in," said Klavan. "At least, it was a change from Vic Damone."