|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

Fabulous

by Gilbert

Millstein, Collier's |

|

In a nervous era of entertainment in which Hollywood has simultaneously embraced the giant screen, the triple screen, the curved screen, three dimensions, Polaroid glasses, no glasses, the single feature and the use of the comparative in preference to the superlative, and the Broadway theater has dabbled diffidently with early curtains, Sunday performances, arena, no scenery, real swimming pools, courtesy at the box office and the use of the superlative in preference to the comparative, a deep thinker in both mediums named Jose Ferrer appears to have hit, at a single gaudy stroke, upon the most splendid gimmick of all--himself. |

Ferrer has exploited this discovery, which he obviously feels is as basic as the wheel and axle, with bursts of energy at once so prodigious and productive that Brooks Atkinson, the drama critic of The New York Times, having once characterized him as "the most able, stimulating and the most versatile actor of his generation in America," was forced to amend the ringing declaration several years later: "He is," Atkinson wrote in plain awe, "the most terrifying man of action in our theater."

There

are those who think that Atkinson, whose main exposure to Ferrer has

been limited largely to performances in a theater or on the screen of

a movie house, understand the case. Not long ago, a friend of

Ferrer's watched the unbound Prometheus, who will be forty-two next

month, for full morning as he supervised production, helped to cast

and prepared to star in four plays for the current season of the New

York City Center (he was directing only three of them) and came away

in a state of sympathetic fatigue. On the way down Seventh Avenue to

Sardi's restaurant for a restorative, he ran into a lady writer named

Inez Karma, who has also had occasion to watch Ferrer in action.

"I saw Joe Ferrer today," said the friend. "Oh,

really," said Miss Karma. "How are they?"

There

are those who think that Atkinson, whose main exposure to Ferrer has

been limited largely to performances in a theater or on the screen of

a movie house, understand the case. Not long ago, a friend of

Ferrer's watched the unbound Prometheus, who will be forty-two next

month, for full morning as he supervised production, helped to cast

and prepared to star in four plays for the current season of the New

York City Center (he was directing only three of them) and came away

in a state of sympathetic fatigue. On the way down Seventh Avenue to

Sardi's restaurant for a restorative, he ran into a lady writer named

Inez Karma, who has also had occasion to watch Ferrer in action.

"I saw Joe Ferrer today," said the friend. "Oh,

really," said Miss Karma. "How are they?"

This impression of multiplicity, which Ferrer cultivates with a sort of informed alertness, and which has divided his friends into psychoanalytical camps--those who are convinced that it arises from an essential insecurity and those who are convinced that it is the result of an equally essential and thoroughly secure ebullience--is almost justified by the facts. It is further reinforced by the extent of his peripheral activities.

Ferrer speaks French, Italian and Spanish, in addition to English, with a fluency that has silenced countless headwaiters...and confounded customs inspectors. While passing through customs some time ago at Orly Field outside Paris--he was then making the motion picture Moulin Rouge, had grown an exotic beard and was wearing an Italian-made suit--he entered into a vivid dispute in French with an inspector over some niggling item. "You, sir," said the inspector at last, "are trying to make a fool of me. You could not possibly be an American." Ferrer was forced ultimately to produce his passport.

HE'S ADDICTED TO TAKING LESSONS

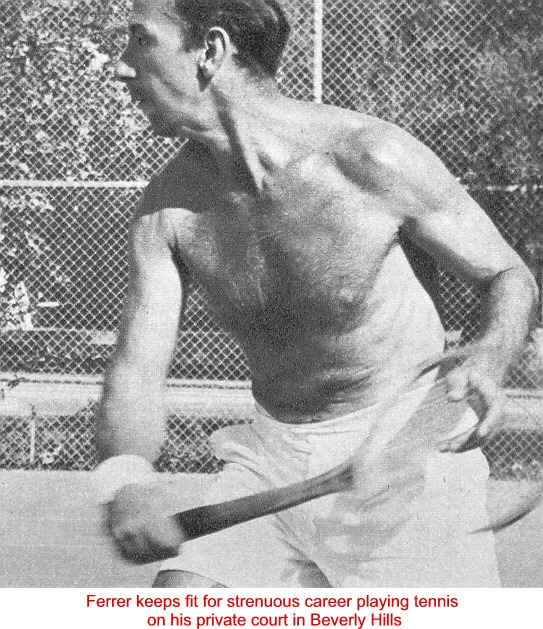

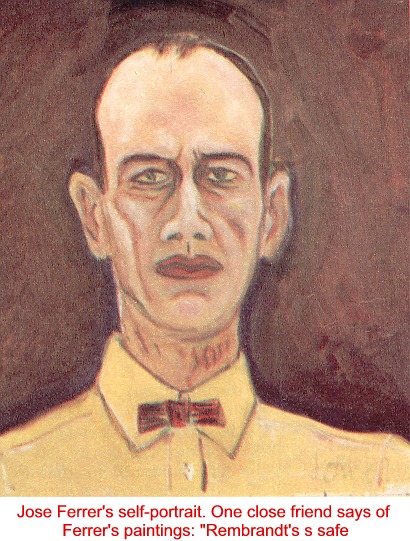

At one time or another, he has take seven tennis lessons in a week, seven in fencing (with either hand), six singing lessons, five in tap dancing, three in yoga, two in judo and two in primitive dancing. He is a painter of some pretensions, a cook and baker of even greater pretensions and a piano player whose range includes both Corelli and Carle (Frankie).

Ferrer

is beyond question the big decathlon man of the theater and motion

pictures and is frequently compared, at least in Hollywood, with

Great Britain's multiple-talented star, Sir Laurence Olivier.

Hollywood sometimes gives him the edge over Olivier on the ground

that while Olivier is better-looking, the United States is a bigger

country. As a matter of fact, where looks are concerned, Sir Laurence

possesses features so regular as to make Ferrer's seem haphazard.

Ferrer

is beyond question the big decathlon man of the theater and motion

pictures and is frequently compared, at least in Hollywood, with

Great Britain's multiple-talented star, Sir Laurence Olivier.

Hollywood sometimes gives him the edge over Olivier on the ground

that while Olivier is better-looking, the United States is a bigger

country. As a matter of fact, where looks are concerned, Sir Laurence

possesses features so regular as to make Ferrer's seem haphazard.

Ferrer's hairline is retreating toward the back of his head with glacial certainty. His ears are uncompromisingly large and set at an angle unfavorable to his head. He has a nose that advances boldly in several directions, in contrast to his chins (he has two) which recede determinedly beneath a large mouth full of prominent but otherwise unnoteworthy teeth. He has a wide chest that outmatches his narrow shoulders, a long waist and short legs. None of these deviations from the Phidian ideal has ever slowed him down, either physically or spiritually. "Joe announces seven projects," a Hollywood director once said admiringly, "and surprises the life out of you by doing six after you've figured out mathematically that he can't possibly manage four."

In the last three years, the period of his most luxurious flowering, Ferrer began by starring in the motion-picture version of Cyrano de Bergarac (for which he later won an Academy Award). He then produced, directed and starred in a revival of Twentieth Century on Broadway; produced and directing Stalag 17; left for Hollywood again, where he starred in Anything Can Happen; made a quick transatlantic flight for the London opening of Cyrano; then returned to Broadway, where he directed The Fourposter; produced, directed and starred in The Shrike (which won the Pulitzer prize as the best American play of 1952) and then produced and directed The Chase. That year, the New York drama critics, in a poll conducted by the trade publication, Variety, selected Ferrer as the best producer, director and actor of 1952; he also won the Donaldson and Antionette Perry Awards for being the best actor and director of last year.

At one point in the spring of 1952, Ferrer was represented on Broadway by four plays, three of which (The Shrike, Stalag 17 and The Chase) were located on the same street, and a motion picture, Anything Can Happen, which was playing around the corner on Times Square. One evening, about ten minutes before curtain time at The Shrike, in which he played, with a great show of verisimilitude, a patient in a mental hospital, Ferrer felt irresistibly impelled to impart a suggestion to the case of The Chase and departed for the other side of the street in costume. He bounded rapidly through traffic, producing an effect, according to an eyewitness, quite as macabre as his performance on stage, since he was wearing only cotton pajamas and felt slippers.

Earlier, when The Chase was in Philadelphia for a tryout, Ferrer had got into the habit of completing his performance in The Shrike every night; catching a train from New York which got him into Philadelphia shortly before two o'clock in the morning; working with the author, Horton Foote, until 5:00 A.M.; sleeping five hours; coaching the cast until late in the afternoon, and catching a train back to New York in time to make his opening curtain on Forty-eight Street. Ferrer passed up these nightly junkets to Philadelphia only twice a week--on the even of The Shrike's matinees.

A PRESCIENT DEAL FOR MOULIN ROUGE

In June of 1952, Ferrer flew to London and worked there and in Paris for four months on Moulin Rouge, in which he portrayed the bearded and shrunken French painter, Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec. The case of Moulin Rouge is probably as striking an illustration as any of Ferrer's particular blend of prescience and practicality.

Two years before the picture was made, he fell into conversation with Hedy Lamarr on the tennis courts at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Miss Lamarr asked Ferrer whether he had read any good books lately and produced a copy of Pierre La Mure's novel, Moulin Rouge. Ferrer, who is unable to thumb over even a seed catalogue without envisioning its dramatic possibilities, read the book and had Miss Lamarr arrange a meeting between him and the author. The upshot was that he bought the dramatic rights and a large share in the screen rights to the novel. A couple of months later, Ferrer, who was then in New York, got a phone call from John Huston, the director, who happened to be in Hollywood. "I thought he was calling from Africa," says Ferrer, who finds himself in deep rapport with anyone who understands the fullest uses of the long-distance telephone.

"Joe," said Houston, "how'd you like to make a picture for me? you know a book called Moulin Rouge? I'm going to buy the rights and make it."

"That's swell, John," Ferrer said. "You might as well talk to me about the rights. I have 'em."

MAKING A TALL MAN INTO A SHORT ONE

Ferrer's preparations for the role of Toulouse-Lautrec were, to say the least, esoteric. Not only did he spend the customary months of research into the character of the great Parisian artist, but he found himself faced with the pressing technical problem that can only confront a man who is five feet ten inches tall planning to play a man who was only four feet eight inches tall.

Ferrer had himself fitted out with a pair of short artificial legs which he had strapped to his knees. (His own lower legs stuck out in back and were kept out of camera range.) Realizing that the straps and the pressure on his knees might cause him a good deal of pain from loss of circulation, he looked up a teacher of yoga on Fifty-fifth Street, and spent some intensive weeks controlling his breathing and jackknifing his body into improbable postures. While this training was not enough to enable him to achieve yoga's goal of ultimate truth or self-levitation, it was sufficient to allow him to wear the legs without passing out every ten minutes.

"It's sensation, man," he has since said of the yoga. (Ferrer, who ran a jazz band at Princeton two decades ago, talks on occasion like a cultivated bop musician. He addresses friends as "pops," "dad" or "gate"' is "fractured" by their jokes, refers to his home as a "crazy little pad"; and professes to be "gone" when something fractures him.) "You want to dig some of that real inside peace it creates. It's not a withdrawal from life at all, simply equips you to cope with it."

One piece of evidence is at hand, however, to indicate that Ferrer had his fleshly envelope pretty well subdued before he ever got around to taking lessons in yoga. Part of Anything Can Happen was filmed in New York in the summer of 1951, and one scene was shot in an ancient Manhattan courthouse. "It was 96 degrees in the streets and I guess it must have been 116 in that courtroom," George Seaton, the director, recalled recently. "This was supposed to be a spring scene and everybody was wearing heavy clothing and pouring sweat. Joe was the only one not perspiring. I asked him how that happened. 'I say to myself, I can't perspire in this scene,' and he had the gall to tell me, 'I'll louse it up.' You know, I don't doubt that Joe Ferrer has the ability to tell his sweat glands, 'Stop, already!'"

Jose fences (either hand), paints, practices yoga and judo

A

NEW SADIE THOMPSON MOVIE

A

NEW SADIE THOMPSON MOVIE

Upon the completion of Moulin Rouge, Ferrer made a couple of rapid trips between Paris, London, New York and Hollywood, and what he calls a "gastronomic tour" of France and Italy, stopping in New York just long enough to direct another hit, My 3 Angels. He was finally caught up with on the West Coast by Columbia Pictures last spring and induced to co-star with Rita Hayworth in Miss Sadie Thompson, the newest version of W. Somerset Maugham's sere and yellowed story of sin in the South Seas, which later became famous on stage and screen as Rain.

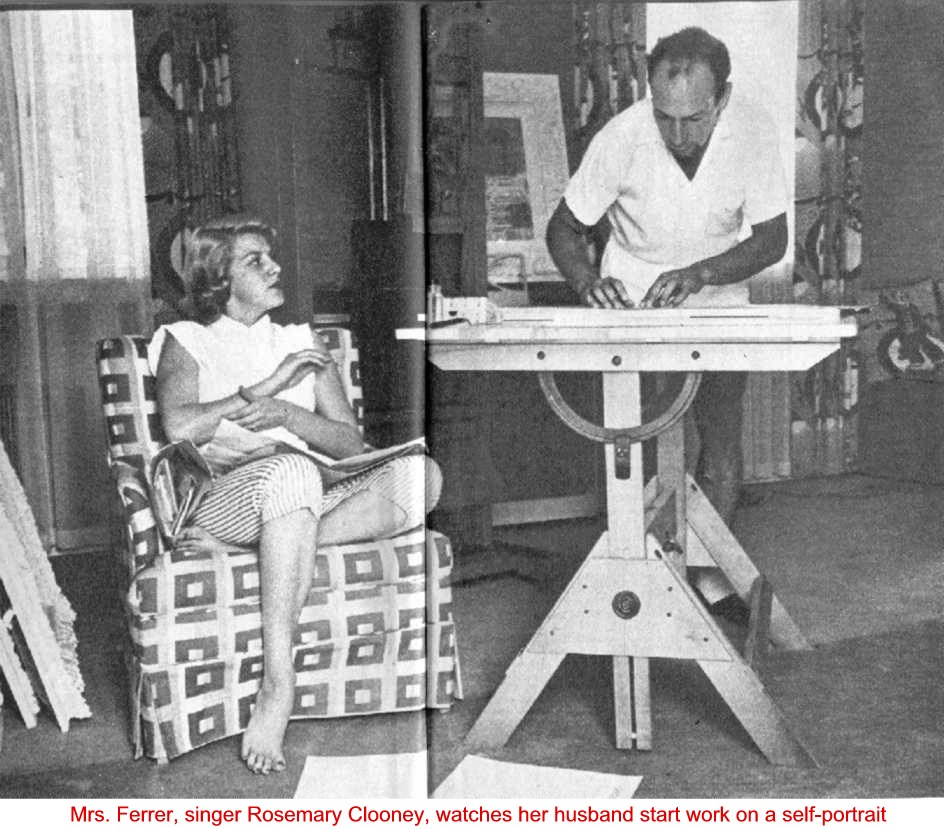

Ferrer had already turned down the part of the morality-ridden reformer. He was in Hollywood, however, to see singer Rosemary Clooney, whom he ultimately made his third wife, and was persuaded by Jerry Wald, the executive producer at Columbia, to drop in and talk things over. There is still some doubt as to who persuaded whom to do what.

"Ferrer didn't want to do it from an artistic standpoint," Milton Pickman, a studio executive, recalls. "He didn't think the original conception of the role would be believable to a present-day audience. We got him down to the office and we went over the script line by line--not only his speeches, but everybody else's. We decided the only way to get this guy was to let him talk.

"We should have had a tape recorder. He talked for four days. The more he talked, the more convinced Wald was that Ferrer was right for the part. Jose made a hundred and eight changes of dialogue in the script; and I don't mean just a line here and a line there, either. After four days, this artistic genius looked up from the chair he was sitting in--he had half a sandwich in his mouth--and he said, 'This is a hell of a role. If somebody does it, this is the way it should be done.' We had him. He literally talked himself into something he wanted no part of."

Ferrer was also talked into accepting $125,000 for his job in the movie, which will be released in January or February of 1954.

During the shooting of Miss Sadie Thompson, Ferrer was signed to play the part of Lieutenant Barney Greenwald in Stanley Kramer's production of The Caine Mutiny. Kramer had been looking for a "tour-de-force actor who could take over in a picture where there had already been a lot of taking-over. I picked Joe because he was the best finale I could think of."

Ferrer is seen only in the last 20 minutes or so of the picture and is preceded on the screen by such outstanding take-over specialists as Humphrey Bogart, Van Johnson and Fred MacMurray. His behavior on the set was, as it has been on other Hollywood sets, completely unexceptionable, even ingratiating.

"it was announced one morning that Ferrer's entrance into the courtroom for the court-martial scene would be filmed. Grips, gaffers, carpenters, property men, actors, extras and all the other crewmen involved were placed in position for the shot, which called for Ferrer to open a door and walk into the room. The set was hushed. The cameras began to turn.

The door opened and Ferrer, whistling the them music from Moulin Rouge, entered on his knees, to which he had tied his shoes.

Like other Hollywood figures faced with a man from the theater who was, in addition to being an actor, a director of considerable stature, Edward Dmytryk, the director of The Caine Mutiny, entertained some private misgivings concerning the Ferrer temperament. "I should have known better," Dmytryk now says. "He's a good director and he knows the value of not interfering. For a man of his stamp, his position, Joe was extremely co-operative. He is sane, rational, pliable and susceptible to direction, although he doesn't need much."

Both Dmytryk and Kramer were repeatedly taken aback by Ferrer's unflagging output and ceaseless motion. "I was lucky to get him," Kramer told an acquaintance in retrospect. "Who knows? He might have been off to Shanghai or somewhere else to do Lord knows what."

Miss Sadie Thompson was completed on June 27th. Shooting of Ferrer's scenes in The Caine Mutiny was scheduled to start on August 8th. That left Ferrer with 42 free days on his hands, a situation he regarded with much the same abhorrence as nature does the vacuum. "Empty time," a Hollywood producer once said of Ferrer, is Joe's only phobia."

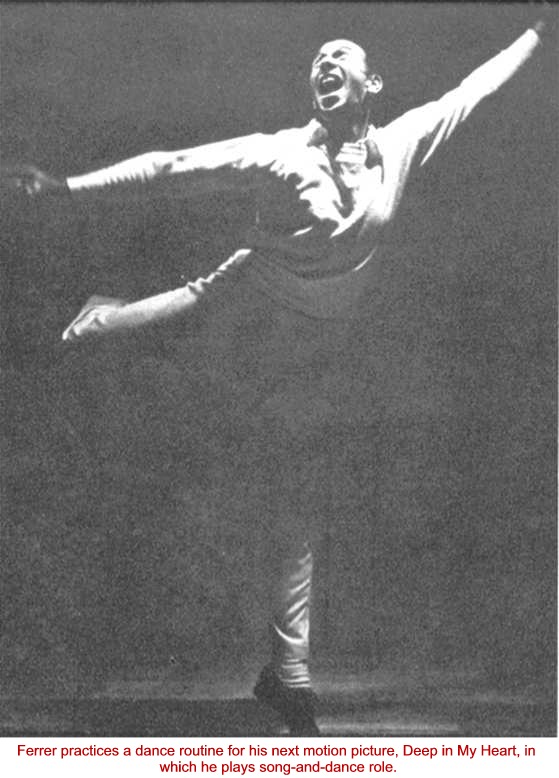

Ferrer quickly restored his psychic balance by agreeing to appear in a singing-dancing role in the musical comedy Kiss Me, Kate, at the State Fair Auditorium in Dallas for two weeks in July. While he has been taking voice lessons on and off for 15 years, Ferrer had sung on the professional stage only twice before. The first time was in a production of No, No, Nanette in St. Louis in 1942. The second time he replaced Danny Kaye in Let's Face It, in 1943, and the show closed three weeks later. His appearance in Dallas was hailed by one influential critic as "his most serious assault on the lyric theater..." The critic found his voice both "audible" and "awful," but conceded that his performance was as "plastic as clay."

Ferrer courted Rosemary Clooney by telephone--from Paris

Characteristically, Ferrer's stay in Dallas was not confined to mere eight performances a week in Kiss Me, Kate. He also took the opportunity to translate a play, The Dazzling Hour, from the French, and collaborate in its adaptation into English, with Ketti Frings, the playwright and screenwriter; rehearse the four principals in the cast for a two-week run at the playhouse in La Jolla, California; compose music for a song for The Dazzling Hour; study the script of The Caine Mutiny; keep in touch with everywhere by long-distance telephone; and get married to Rosemary Clooney in Durant, Oklahoma, 96 miles north of Dallas, shortly after being divorced by his second wife, Phyllis Hill, the actress. He missed neither a performance of Kiss Me, Kate nor a rehearsal of The Dazzling Hour.

"CUTE IDEA" BECOMES A SONG

A month later, on the basis of having written one song, he set up a music publishing company. "When I arrived in Dallas," Miss Frings says, "I had an idea for the lyrics for the song. One day, we were taken to lunch at Neiman-Marcus. Afterward we were going down the elevator on our way back to the hotel and I handed Joe a slip of paper with the lyrics on it. He read it and said, 'Cute idea,' and put it in his pocket.

"We got back to the hotel and I couldn't have been in my room for more than ten minutes when the phone rang. It's Joe. 'I think I've got a tune,' he says, and hums the refrain. 'Get that down fast,' I yelled at him. 'Oh, I've already got it down,' he said. I was flabbergasted."

Ferrer has now reached a stage in his career where he is pulled and hauled at by two cities, New York and Los Angeles. While these are five fewer than claimed Homer, an older celebrity whose only racket was writing, they are considerably more strident in their demonstrations.

Thus, at one time or another, he has been accused on Broadway of "garroting the living theater" by going to Hollywood to make moving pictures, and in Hollywood of evading his manifest destiny by returning to Broadway to do plays. Along Broadway, a number of the artier members of his profession have detected what they term a growing "externalization," or "surface quality," in his acting, while in Hollywood a couple of directors felt that he had a tendency--which they helpfully corrected--to be too "cerebral." He has been criticized on both coasts for attempting to do too much and denounced as "commercial" for succeeding. A close friend of Ferrer's, who has been blown about by these winds of dissension at a succession of parties, undertook recently to defend him.

RESENTMENT BORN OF ENVY

"Nobody likes Joe," he began, "but the audience. People are envious, jealous and annoyed by his versatility. They say, 'He'll fall on his face somewhere along the line.' But he's one of the few producers who really produce; one of the few actors who really act; one of the few directors who really direct. People resent a man with so much apparent control, a man who gets up at a party at 10:30 and says, 'I'm going home. I've got work to do.'"

It is Ferrer's own opinion that he is merely driving, himself toward what he calls the "maximum possible dramatic expression," and that he is just doing what he likes to do. "I'm lucky," he said, some time ago. "I picked a field that's fun for me. For me to lift a finger at something I don't like to do is just agony. I'm the laziest, most incompetent guy in the world at something I don't like to do."

Nevertheless, at forty-one, he is beset with intimations of mortality which can be set off by nothing more than the sight of his thinning hair in a mirror. "With Moulin Rouge, I turned the corner," he went on with the smallest trace of tragedy in his voice. "I was no longer a kid after that. I couldn't fool. I couldn't adlib any longer."

This gloomy reverie was delivered by Ferrer on the patio of his residence in Beverly Hills (he has a home in Ossining, New York, as well as an apartment in Manhattan), an enormous Spanish mission affair, which includes a swimming pool and a tennis court. Ferrer had just played several sets of tennis, had showered and shaved and was vigorously at work on a steak.

"I've got to the point in my life now," Ferrer said, "where I don't particularly kid about my career. In the last few months, I've had a terrible awareness of the shortness of time, of impending death. I guess it's because I feel my days as a leading actor are coming to a close. I don't want to be the most beloved character actor in the business. I sometimes get so depressed at the thought of the curtailment of my physical activities. What I do is try to think about it and find some logical adjustment to the situation that will leave me in peace."

A month later, he was doing Cyrano de Bergerac, The Shrike, Richard III and Charley's Aunt at the New York City Center.

About the beginning of February, Ferrer expects to return to Hollywood to sing and dance in a picture for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer called Deep In My Heart, which is the life story of the composer, Sigmund Romberg. After that, he may produce, direct, and star in the screen version of The Shrike.

It is only in recent years that Ferrer's earnings have kept pace with his professional advance. As recently as 1939, he earned $5,400. He did not achieve the six-figure bracket until 1950. In the last two years, he earned about a quarter of a million dollars a year (roughly the same as Miss Clooney's current earnings).

Poverty, however, has never been one of Ferrer's more pressing problems. His father, Rafael, was an attorney who lived in Santurce, Puerto Rico, where Jose Vincente Ferrer y Cintron was born on January 8, 1912. His mother, Maria, came of a family of wealthy plantation owners. Ferrer's mother died 25 years ago and his father, who remarried, died in 1951. Their estate, a considerable one, was divided among Ferrer, his two sisters and a half brother.

For a future man of the theater, Jose Ferrer's natal equipment was something less than adequate. He was born with a cleft soft palate and he might have developed a speech impediment had he not been taken to New York at the age of seven months for an operation.

When Ferrer was six years old, his family settled in New York and he attended public and private schools there and in Switzerland before entering Princeton in 1928.

"He was far above most Princeton men in charm, talent and cultivation," Joshua Logan, another formidable theater man, who was at college with Ferrer, says. "He was the guy who completely licked the place. They resisted him like they would resist any exotic element. He never bowed down before the golden calves of Princeton and because of that he was an outstanding Princeton man. By the time he left, people were panting to be considered his friend."

Ferrer exerted his charm, talent and cultivated tastes in so many areas, however, that it took him five years to graduate, during the course of which he neglected his major study, architecture, did a good deal of drinking in New York speak-easies and made a smash hit in a Triangle Club production in his second senior year.

White at college, he organized his jazz band, known as the Pied Pipers, which occasionally employed the services of a tall student named James Stewart, who played the accordion and sang, and who has since become an actor, too. In 1930, Ferrer became the only bandleader, undergraduate or otherwise, to stop a ship in mid-ocean.

He had taken the Pied Pipers on a summer tour of Europe and was returning on the French Liner, Rochambeau, when the ship ran into a fog. Ferrer picked up a Flugelhorn, stuck it out of a porthole and blew on it with an intensity mournful enough to make the ship's officers believe they were about to collide with another vessel. "First thing I knew," Ferrer said later, "there were hands on my shoulders and a lot of blue serge and gold braid surrounding me. Nobody got thrown in irons, though."

After

a year of post-graduate work in French at Princeton and another year

on some recondite aspects of the Belgian novel at Columbia, Ferrer

found himself enjoying life, in the main, but getting nowhere. Over a

bottle of wine in a Greek restaurant in Manhattan, he announced to

Stewart one night that he was going into the theater.

After

a year of post-graduate work in French at Princeton and another year

on some recondite aspects of the Belgian novel at Columbia, Ferrer

found himself enjoying life, in the main, but getting nowhere. Over a

bottle of wine in a Greek restaurant in Manhattan, he announced to

Stewart one night that he was going into the theater.

He began by driving a station wagon for Joshua Logan, who was then directing a summer theater at Suffern, New York. Three years later, he married Uta Hagen, the actress. The couple had a daughter, Leticia, who is now thirteen. (Miss Hagan and Ferrer were divorced in 1948.)

Ferrer did not reach stardom until 1940, when he took the lead in a revival of the old romp, Charley's Aunt, and caused a sensation with his performance, which mainly consisted of swinging from walls to trees while smoking a cigar and wearing women's dresses.

In 1943 on Broadway he attained what was probably his greatest artistic achievement, playing Iago to Paul Robeson's Othello.

About the only untoward event in Ferrer's spectacular rise was a brush with the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951. When the committee questioned some of Ferrer's past associations with Communist front organizations, he went to Washington and swore unhesitatingly that he had never been a Communist. His testimony seemed to satisfy all concerned, and the incident did not cause any noticeable check in his career.

ROSIE PLAYED ALOOF--AT FIRST

Almost nothing has--including his marriage to Rosemary Clooney. Ferrer and Miss Clooney met in New York three years ago when both of them appeared on a television show. "I rather thought she didn't like me," he says now. "She seemed very aloof. It was just hello and good-by." Miss Clooney liked Ferrer just fine. Hello and good-by developed into a serious attachment as the months passed. Much of the courtship was pursued, as might have been expected of Ferrer, over the long-distance telephone, when he was in Paris making Moulin Rouge and Miss Clooney was in Hollywood.

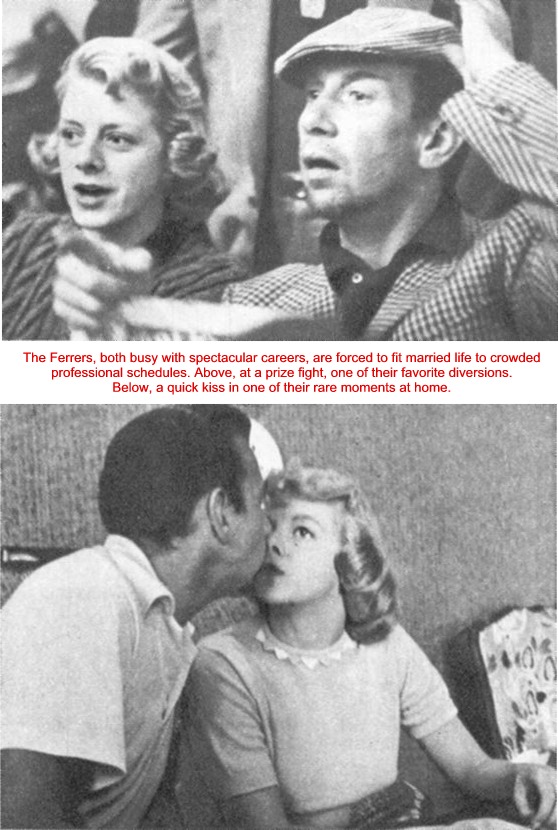

To date, their married life has been conspicuously affectionate, though also somewhat sketchy. When he is not working on a picture or a play, she is working on a picture, making records or doing radio shows. During their rare moments together at home they have made a valiant stab at domesticity. They watch television; they read; they go out to an occasional prize fight. Recently, it was reported, they acquired a 50 per cent interest in a fighter. Miss Clooney neither sings nor dances at home, since she considers such activities to be business matters. ("I am perfectly wiling to sing in front of her," her husband says.)

Miss Clooney is convinced that marriage to Ferrer, despite the separations that are inevitable in a pair of highpowered careers, is "the most stimulating thing in the world." After a moment of reflection, she adds, "It can be discouraging, too--the things you do for a living, he does better as hobbies." Ferrer takes a more cheerful view of the union. "Rosie," he told a friend a couple of weeks ago, "is absolutely gone."