"Rosemary Clooney"

Back from the razor's edge of addiction and breakdown,

she's older, wiser and the inspiration for new TV movie

by Sarah Pileggi

PEOPLE - December 13, 1982

On

a summer night in 1968 Rosemary Clooney, fueled by Seconal and mounting insanity,

drove her white Cadlilac Eldorado up the wrong side of a winding, two-lane

mountain road In Nevada, intent, in her disintegrating state of mind, on

testing God's love. If He let her court death all the way from Reno to Lake

Tahoe and survive, it would mean that He loved her.

On

a summer night in 1968 Rosemary Clooney, fueled by Seconal and mounting insanity,

drove her white Cadlilac Eldorado up the wrong side of a winding, two-lane

mountain road In Nevada, intent, in her disintegrating state of mind, on

testing God's love. If He let her court death all the way from Reno to Lake

Tahoe and survive, it would mean that He loved her.

"That's one for you, God," she shouted triumphantly as the headlights

of approaching cars veered from her suicidal path. Earlier, from the stage

of Harold's Club in Reno, Clooney had raged incoherently at a stunned nightclub

audience, then stalked off the stage, leaving the band to play her signature

number, Come On-a My House, without her.

God, fate or plain Irish luck interceded that night, and Clooney lived

to sing again. Testifying to her survival is Rosie: The Rosemary Clooney

Story, the CBS movie, airing Dec. 8, that is based on the singer's 1977

autobiography, This for Remembrance. For the sound track, Clooney recorded

some two dozen numbers in the inimitable husky voice that lit up the '50s.

Some are songs Clooney made famous. Some are band numbers that she and her

late sister, Betty, sang in the '40s, when they were touring with Tony Pastor's

band. And some, like Goody-Goody, filmed in live performance at London's

Royal Festival Hall, are staples of Clooney's lately revived career as a

grande dame of American pop.

For

four years after her 1968 breakdown, as she underwent five-days-a-week

psychoanalysis, Clooney sang much less. She was tired of performing. The

joy was gone from her work and had been for some time. She sang because she

needed the money, but "the more removed I became from my feelings, the less

I sang well," she says now. "There are some records I made with Frank Sinatra

then that I hate. I knew they were bad when I was making them, but there

was nothing I could do about it. I could not sing any better than I was singing."

For

four years after her 1968 breakdown, as she underwent five-days-a-week

psychoanalysis, Clooney sang much less. She was tired of performing. The

joy was gone from her work and had been for some time. She sang because she

needed the money, but "the more removed I became from my feelings, the less

I sang well," she says now. "There are some records I made with Frank Sinatra

then that I hate. I knew they were bad when I was making them, but there

was nothing I could do about it. I could not sing any better than I was singing."

When at last she could sing better, she found to her dismay that her

lackluster performances of recent years, combined with the aberrant behavior

in the months preceding her collapse—irrational outbursts, rages, delusions

of persecution—had left a legacy of mistrust among promoters and nightclub

owners that canceled out more than two decades of exemplary professionalism.

"A lot of damage was done in a short period, and it's terrifically hard to

undo it," she says. "There wore rumors of alcoholism, of pill

addiction—they were right on that one—even that I had a fatal disease.

People who had hired me before no longer wanted me."

For

Clooney, unemployment was a new kind of emptiness. Work had been the one

constant in her life since 1945, when she and Betty, both still in school,

got their first job, singing duets on WLW Radio in Cincinnati. Soon afterward

they began singing with local bands, and in 1947, as the Clooney Sisters,

they joined Pastor on the road. They made their debut in matching homemade

dresses at the Steel Pier in Atlantic City.

For

Clooney, unemployment was a new kind of emptiness. Work had been the one

constant in her life since 1945, when she and Betty, both still in school,

got their first job, singing duets on WLW Radio in Cincinnati. Soon afterward

they began singing with local bands, and in 1947, as the Clooney Sisters,

they joined Pastor on the road. They made their debut in matching homemade

dresses at the Steel Pier in Atlantic City.

After two years of one-night stands, Betty returned to Cincinnati (she

died in 1976 of aneurysms) while Rosemary struck off on her own. It was 1949,

and the big-band era was coming to an end. Now the singers were the stars.

It was Mitch Miller, the benevolent Svengali of Columbia Records, who made

Clooney a household name in 1951 by insisting she record Come On-a My House,

a novelty tune, with lyrics by William Saroyan, that Clooney cordially

detested.

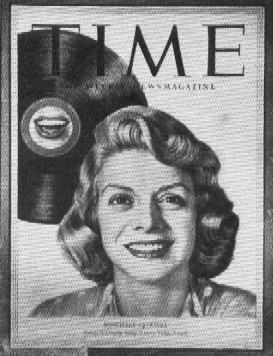

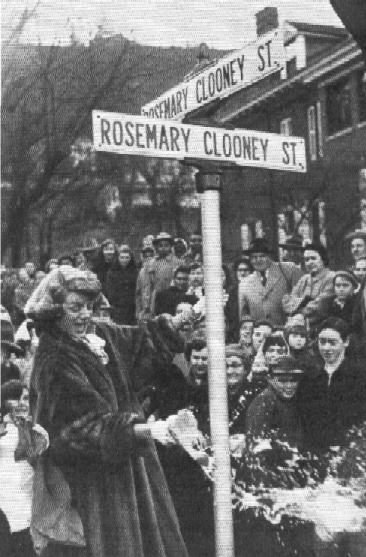

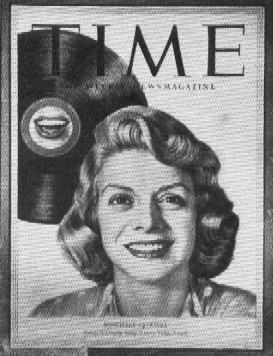

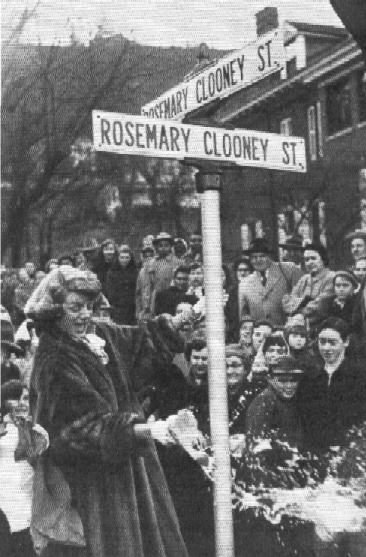

With a hit behind her and Columbia s publicity mill churning in her behalf,

the blue-eyed blonde from Maysville, Ky. found herself New York's favorite

new-girl-in-town. Her face was on the cover of TIME, and the men in her lite

were famous too—TV's Dave Garroway and Robert Q. Lewis and actor Jose

Ferrer. Then, in 1952, Clooney signed a movie contract with Paramount. The

studio's publicity writers called her "the next Betty Hutton," and the money

rolled in.

"I

remember the first really huge royalty check I ever got," says Clooney. "It

was for $130,000. But that's the last one I think I ever held in my hand,

because at that point you get on such a merry-go-round and there are so many

people doing everything for you—paying your bills, answering your phone,

taking care of money coming in and going out. I just knew that it was fine,

and that somebody would tell me when I didn't have enough money to do something."

"I

remember the first really huge royalty check I ever got," says Clooney. "It

was for $130,000. But that's the last one I think I ever held in my hand,

because at that point you get on such a merry-go-round and there are so many

people doing everything for you—paying your bills, answering your phone,

taking care of money coming in and going out. I just knew that it was fine,

and that somebody would tell me when I didn't have enough money to do something."

In 1953 Clooney, 25, married the recently divorced Ferrer, 16 years her

senior. The marriage was her first. his third. Their son Miguel was born

in 1955, and Clooney had her first platinum record—Hey There, with This

Ole House on the flip side. From 1956 to 1960 she had four more children

and two TV series. Fan magazines of the day portrayed the singer as the

all-American mother, a tower of smiling strength, able to juggle marriage,

children and a glamorous career without missing a beat. In fact, the strain

was beginning to tell. Ferrer, though a good and attentive father, was a

dedicated womanizer, Clooney later testified in court. And Clooney was

increasingly torn between what she felt she owed her children and what her

advisers convinced her she owed her career. With her loyalties divided, her

pleasure in her work seeped away, and her performances suffered accordingly.

Sleeping pills became a nightly routine for her.

Eventually

Ferrer and Clooney werc divorced, first in 1961, then again in 1967 after

an abortive three-year reconciliation. "He's one of the most talented men

alive at concentrating on what he's doing," she said at the time. "He can

shut the whole world out. That's a rough thing to do to your wife and five

children." Though Clooney continued to work, her career was on a downward

course, and her dependence on pills had grown into a full-fledged addiction

to Seconal, Tuinal, Valium and Percodan.

Eventually

Ferrer and Clooney werc divorced, first in 1961, then again in 1967 after

an abortive three-year reconciliation. "He's one of the most talented men

alive at concentrating on what he's doing," she said at the time. "He can

shut the whole world out. That's a rough thing to do to your wife and five

children." Though Clooney continued to work, her career was on a downward

course, and her dependence on pills had grown into a full-fledged addiction

to Seconal, Tuinal, Valium and Percodan.

When the breakdown finally came, Clooney was 40. Her slide into unreality

began when her drummer and young lover of two years abruptly walked out of

her life. The disintegration continued when her friend Robert Kennedy was

shot down only yards from where Clooney was standing with two of her children.

Then came her mad drive up he mountain and her subsequent confinement in

the psychiatric ward at Mount Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles.

Part Two of the Rosemary Clooney story began in 1972 at the Tivoli Gardens

in Copenhagen. It was a warm summer night, and the park was ablaze with little

white lights. For the first time in years, performing felt good. After that

her progress was slow but steady. She faced her first big U.S. audience at

the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion In Los Angeles on St. Patrick's Day, 1976.

Bing Crosby was launching a tour to mark his 50th anniversary in show business,

and he had asked Rosie to join him. The evening was a sellout, the reviews

complimentary. Later Clooney signed a recording contract with Concord, a

small but prestigious jazz label; she was hired by Georgia-Pacific to advertise

products like Coronet paper towels and tissues; and she became one-fourth

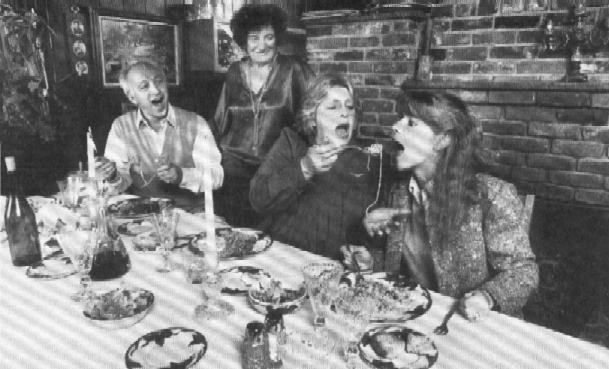

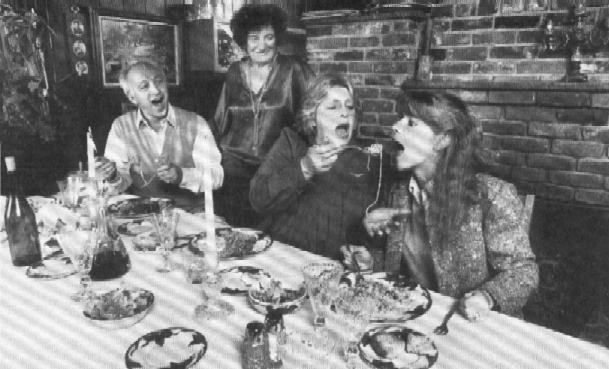

of a surprisingly successful road show called 4 Girls 4 that has been touring

concert halls and summer music tents since 1977. The current troupers are

Clooney, Helen O'Connell, Kay Starr and Martha Raye.

"It's a very small responsibility to be a fourth

of something," says Clooney, who still attends group therapy sessions on

Wednesday evenings when she's home in California, "and it's a wonderful company

feeling. We have exactly the same backgrounds. We've been in show business

since we were kids. We've all been married. We all have children and

grandchildren. We were never told in the '50s that the people we were going

to have the most fun working with would be other women. You were trained

to think that women would be out for your job, and certainly your man."

"It's a very small responsibility to be a fourth

of something," says Clooney, who still attends group therapy sessions on

Wednesday evenings when she's home in California, "and it's a wonderful company

feeling. We have exactly the same backgrounds. We've been in show business

since we were kids. We've all been married. We all have children and

grandchildren. We were never told in the '50s that the people we were going

to have the most fun working with would be other women. You were trained

to think that women would be out for your job, and certainly your man."

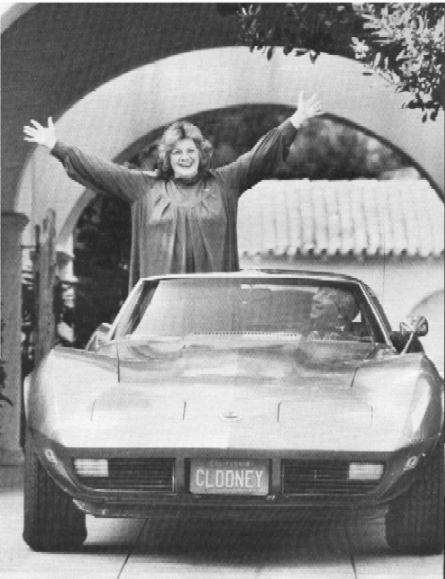

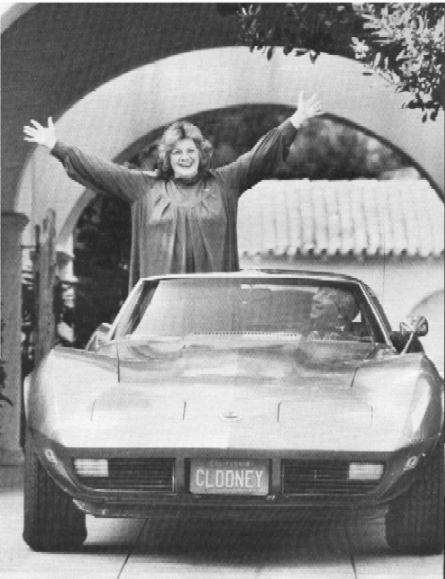

Clooney's constant companion those days is a tall, slim former dancer,

Dante DiPaolo, 55, a flame from her earliest Hollywood days who dropped back

into her life in 1973 and has been there ever since. In spite of the weight

she has gained since the time when too many pills and too much work kept

her thin, Clooney's health is intact. "My constitution must have been

remarkable," she says, "because I put my body through some trying times."

Her hair is a darker, natural blond now, her grin still dazzles, her laughter

is hearty and frequent, and, as a reviewer observed not long ago, at 54,

she still has nice legs.

Best of all, the voice that made Clooney's fortune is unsavaged by age

and her trials. Her six recordings for Concord, with a small group of jazz

men behind her, have revealed new feeling and sensitivity, adding subtle

colors to her old lusty style. Whenever Clooney sings now, whether in a

California recording studio or a summer tent in upstate New York, the joy

is visibly, audibly back. "I had it in the beginning," she says, "but from

a certain point on, my thoughts and feelings were always divided. I worked

very hard, sometimes pregnant, sometimes right after being pregnant, and

I was always being taken away from a baby."

Though she is delighted with her jazz group, and the feeling is apparently

mutual, she tends to brush off reviewers who call her a jazz singer. "I don't

think I am, because what I do isn't very inventive," she says frankly. "I

don't have that much good musicianship, and I don't know what I'm doing,

really. I just feel things a certain way, and I'll get thrown into a certain

kind of phrasing from something the band will do."

The

Ferrer children are grown now, and, not surprisingly, all lean toward show

business. Miguel, 27, a drummer who has occasionally played with his mother's

backup band, and Rafael, 22, an actor whose credits include a bit part in

Woody Allen's A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy, live at home in the big, cool,

dark Spanish-style house in Beverly Hills that Clooney bought almost 30 years

ago. The others live only minutes away and visit almost every day. Maria,

26, recently returned from New York, where she studied acting. Monsita, 24,

a talented singer who has not yet tested herself professionally, has made

a couple of TV commercials and acts as her mother's executive secretary.

She is married to Terry Botwick, a former minister turned writer-producer.

Gabriel, 25, a sculptor, painter and pianist, is wed to singer Debby Boone.

They have a 21/2 year-old boy, Jordan, who is Clooney's first grandchild

and the light of her life. He is kissed several hundred times a day and thrives

on it.

The

Ferrer children are grown now, and, not surprisingly, all lean toward show

business. Miguel, 27, a drummer who has occasionally played with his mother's

backup band, and Rafael, 22, an actor whose credits include a bit part in

Woody Allen's A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy, live at home in the big, cool,

dark Spanish-style house in Beverly Hills that Clooney bought almost 30 years

ago. The others live only minutes away and visit almost every day. Maria,

26, recently returned from New York, where she studied acting. Monsita, 24,

a talented singer who has not yet tested herself professionally, has made

a couple of TV commercials and acts as her mother's executive secretary.

She is married to Terry Botwick, a former minister turned writer-producer.

Gabriel, 25, a sculptor, painter and pianist, is wed to singer Debby Boone.

They have a 21/2 year-old boy, Jordan, who is Clooney's first grandchild

and the light of her life. He is kissed several hundred times a day and thrives

on it.

When she is not touring, Clooney observes the passing parade of children

from her favorite leather chair and ottoman in the den between the living

room and the old-fashioned kitchen through which all but total strangers

enter. She is the heart of the household. Her outlook is positive, and she

seems at peace, as long as she can govern the pace of her life. She explains,

"My therapist told me, 'Block out time, even if it's only one day. That's

time for you.' "

Though Clooney was brought up Catholic and sent her children to a parochial

grade school, all the children except Rafael are deeply involved in religion

that is Protestant and evangelical. Mother does not disapprove. "It's no

problem for me," she says. "I see them being very productive and happy in

an ongoing spiritual relationship with each other and with Jesus in a way

that they wouldn't have in a dogmatic religion. Catholicism was always ritual

and removed, and they seem to have a very personal and warm feeling. I don't

have the real commitment they have," she admits, with the caution of a woman

to whom life has taught skepticism. "But I'd like for it to happen, and maybe

it will."

On

a summer night in 1968 Rosemary Clooney, fueled by Seconal and mounting insanity,

drove her white Cadlilac Eldorado up the wrong side of a winding, two-lane

mountain road In Nevada, intent, in her disintegrating state of mind, on

testing God's love. If He let her court death all the way from Reno to Lake

Tahoe and survive, it would mean that He loved her.

On

a summer night in 1968 Rosemary Clooney, fueled by Seconal and mounting insanity,

drove her white Cadlilac Eldorado up the wrong side of a winding, two-lane

mountain road In Nevada, intent, in her disintegrating state of mind, on

testing God's love. If He let her court death all the way from Reno to Lake

Tahoe and survive, it would mean that He loved her.

For

four years after her 1968 breakdown, as she underwent five-days-a-week

psychoanalysis, Clooney sang much less. She was tired of performing. The

joy was gone from her work and had been for some time. She sang because she

needed the money, but "the more removed I became from my feelings, the less

I sang well," she says now. "There are some records I made with Frank Sinatra

then that I hate. I knew they were bad when I was making them, but there

was nothing I could do about it. I could not sing any better than I was singing."

For

four years after her 1968 breakdown, as she underwent five-days-a-week

psychoanalysis, Clooney sang much less. She was tired of performing. The

joy was gone from her work and had been for some time. She sang because she

needed the money, but "the more removed I became from my feelings, the less

I sang well," she says now. "There are some records I made with Frank Sinatra

then that I hate. I knew they were bad when I was making them, but there

was nothing I could do about it. I could not sing any better than I was singing."

For

Clooney, unemployment was a new kind of emptiness. Work had been the one

constant in her life since 1945, when she and Betty, both still in school,

got their first job, singing duets on WLW Radio in Cincinnati. Soon afterward

they began singing with local bands, and in 1947, as the Clooney Sisters,

they joined Pastor on the road. They made their debut in matching homemade

dresses at the Steel Pier in Atlantic City.

For

Clooney, unemployment was a new kind of emptiness. Work had been the one

constant in her life since 1945, when she and Betty, both still in school,

got their first job, singing duets on WLW Radio in Cincinnati. Soon afterward

they began singing with local bands, and in 1947, as the Clooney Sisters,

they joined Pastor on the road. They made their debut in matching homemade

dresses at the Steel Pier in Atlantic City.

"I

remember the first really huge royalty check I ever got," says Clooney. "It

was for $130,000. But that's the last one I think I ever held in my hand,

because at that point you get on such a merry-go-round and there are so many

people doing everything for you—paying your bills, answering your phone,

taking care of money coming in and going out. I just knew that it was fine,

and that somebody would tell me when I didn't have enough money to do something."

"I

remember the first really huge royalty check I ever got," says Clooney. "It

was for $130,000. But that's the last one I think I ever held in my hand,

because at that point you get on such a merry-go-round and there are so many

people doing everything for you—paying your bills, answering your phone,

taking care of money coming in and going out. I just knew that it was fine,

and that somebody would tell me when I didn't have enough money to do something."

Eventually

Ferrer and Clooney werc divorced, first in 1961, then again in 1967 after

an abortive three-year reconciliation. "He's one of the most talented men

alive at concentrating on what he's doing," she said at the time. "He can

shut the whole world out. That's a rough thing to do to your wife and five

children." Though Clooney continued to work, her career was on a downward

course, and her dependence on pills had grown into a full-fledged addiction

to Seconal, Tuinal, Valium and Percodan.

Eventually

Ferrer and Clooney werc divorced, first in 1961, then again in 1967 after

an abortive three-year reconciliation. "He's one of the most talented men

alive at concentrating on what he's doing," she said at the time. "He can

shut the whole world out. That's a rough thing to do to your wife and five

children." Though Clooney continued to work, her career was on a downward

course, and her dependence on pills had grown into a full-fledged addiction

to Seconal, Tuinal, Valium and Percodan.

"It's a very small responsibility to be a fourth

of something," says Clooney, who still attends group therapy sessions on

Wednesday evenings when she's home in California, "and it's a wonderful company

feeling. We have exactly the same backgrounds. We've been in show business

since we were kids. We've all been married. We all have children and

grandchildren. We were never told in the '50s that the people we were going

to have the most fun working with would be other women. You were trained

to think that women would be out for your job, and certainly your man."

"It's a very small responsibility to be a fourth

of something," says Clooney, who still attends group therapy sessions on

Wednesday evenings when she's home in California, "and it's a wonderful company

feeling. We have exactly the same backgrounds. We've been in show business

since we were kids. We've all been married. We all have children and

grandchildren. We were never told in the '50s that the people we were going

to have the most fun working with would be other women. You were trained

to think that women would be out for your job, and certainly your man."

The

Ferrer children are grown now, and, not surprisingly, all lean toward show

business. Miguel, 27, a drummer who has occasionally played with his mother's

backup band, and Rafael, 22, an actor whose credits include a bit part in

Woody Allen's A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy, live at home in the big, cool,

dark Spanish-style house in Beverly Hills that Clooney bought almost 30 years

ago. The others live only minutes away and visit almost every day. Maria,

26, recently returned from New York, where she studied acting. Monsita, 24,

a talented singer who has not yet tested herself professionally, has made

a couple of TV commercials and acts as her mother's executive secretary.

She is married to Terry Botwick, a former minister turned writer-producer.

Gabriel, 25, a sculptor, painter and pianist, is wed to singer Debby Boone.

They have a 21/2 year-old boy, Jordan, who is Clooney's first grandchild

and the light of her life. He is kissed several hundred times a day and thrives

on it.

The

Ferrer children are grown now, and, not surprisingly, all lean toward show

business. Miguel, 27, a drummer who has occasionally played with his mother's

backup band, and Rafael, 22, an actor whose credits include a bit part in

Woody Allen's A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy, live at home in the big, cool,

dark Spanish-style house in Beverly Hills that Clooney bought almost 30 years

ago. The others live only minutes away and visit almost every day. Maria,

26, recently returned from New York, where she studied acting. Monsita, 24,

a talented singer who has not yet tested herself professionally, has made

a couple of TV commercials and acts as her mother's executive secretary.

She is married to Terry Botwick, a former minister turned writer-producer.

Gabriel, 25, a sculptor, painter and pianist, is wed to singer Debby Boone.

They have a 21/2 year-old boy, Jordan, who is Clooney's first grandchild

and the light of her life. He is kissed several hundred times a day and thrives

on it.